Constructing Ideas or Collecting Information?

What do fact collectors have in common with used bookstore owners?

Answer: neither one knows for certain what they have in stock.

When I say “fact collector” I’m not talking about an unusual hobby. Fact collecting is normative for the typical student in the typical classroom. Unfortunately for learning, our brains are not built to retain facts except, perhaps through grinding drill and repetition.

The solution is to recognize that ideas are the means of bundling facts and giving them meaning. The brain is magnificent at creating and connecting ideas!

What follows is an approximate transcript of the podcast “Constructing Ideas or Collecting Information?”

Intro:

How can your help your child thrive as a learner if they are in an educational system that is chiefly successful at killing the joy of learning? That’s not hyperbole. Most children are in a desert that the late Sir Ken Robinson called education’s death valley. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wX78iKhInsc

Few emerge on the other side of this valley with their curiosity and desire to know and understand intact. This season of podcasts is designed to enable you to be a guide to help your children not just survive but thrive.

The past two episodes have dealt with the fatal focus on facts in educational systems as demonstrated by the inability of the brain to hold onto them and build on them. Today’s podcast will help you distinguish between information and ideas and then to develop, deepen understanding of, and logically connect ideas.

Today we’ll be interrogating cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham’s learning principle number 4:

“We understand new things in the context of things we already know.”

Podcast:

The framework for this season comes from 10 principles of learning laid out in cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham’s practical book, Why Don’t Students Like School?

Today we’re going to tackle how to help your child move from absorption with taking in information to a fixation on understanding ideas. This is key to durable learning that is extensible; learning that you can build on and apply to solving real world problems.

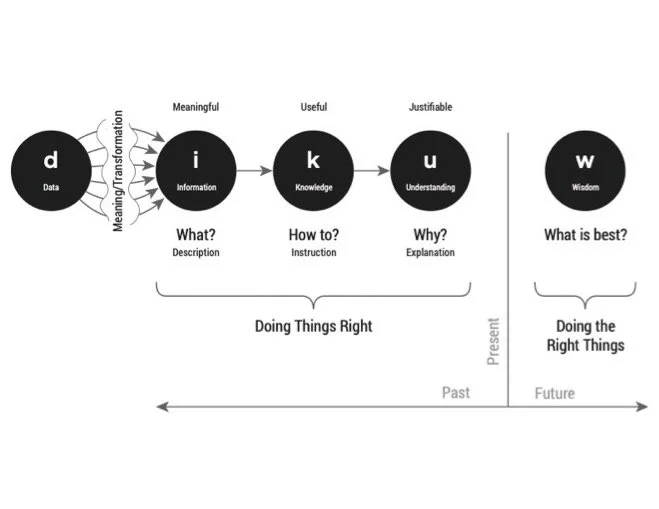

To give some context l want to go back to something I’ve developed in previous seasons of this podcast. The acronym is DIKUW. The D stands for data. Perhaps you’re old enough to remember when what we now call IT was called Data Processing. Data consists of important specifics like telephone numbers or e-mail addresses. Computers are good at processing data, but humans are not. We need data to be transformed so that it has meaning. Associating names of people with their e-mail addresses gives meaning. Building a database that includes more specifics like street address, marital status, credit history, etc. puts even more data into meaningful alignment. The point here is that learning is not even feasible if we try to learn something that has no meaning. Everyone gets that. Humans must grapple with information, not data.

A synonym for information is facts. It is a fact that the low temperature last night was 17° F where I live in SC. It is a fact that Donald Trump was inaugurated Jan. 20th, 2025, for his second term in office. It is a fact that he is only the second president in history to be elected to two discontinuous terms. Facts are true statements. Educational systems tend to focus on creating a memory of facts. It is also a fact that the brain doesn’t do well remembering facts!

In DIKUW, K is knowledge. To know something is more than the ability to retrieve it on command. To know means I can explain it. What is this “It” that I can explain? We have to move to an idea if explanation is the goal. Ideas bundle related ideas together. Take 17° F. It makes no sense to say, “Explain 17° F.” If you insist on an explanation, I’ll bundle 17° with the Fahrenheit temperature scale as well as with the fact that water freezes at 32° F and 17° is smaller, so it is even colder. When I do this, I’m in the realm of ideas.

Human minds don’t do data

What we have so far is that human minds don’t do data. Our brains require meaning so data needs to be transformed into something meaningful which we call information. If you ask if I know something, we’ll have to jump to another level called an idea. Ideas are bundles of related facts tied up with an explanation. Reproducing the information bundle without being able to explain how the facts in the bundle relate to each other is not knowledge. Perhaps this helps explain why I’m bothered by Willingham’s hybrid “factual knowledge” referenced in the previous podcast or another monstrosity in his chapter 4 that he calls “rote knowledge.” Memorization of something that is meaningless is “rote.” If it is meaningless, it can’t be explained.

The rest of DIKUW refers to “U,” understanding and “W,” wisdom. These are attributes of deeper knowledge. We don’t need to talk about those yet.

Unlike isolated facts which the brain stores only with great difficulty and usually very temporarily, ideas—the bundles of related facts tied up with an explanation are what the brain uses to transact the business of thinking. Ideas do not exist in isolation. Ideas relate to other ideas. The nature and number of these relationships creates a network or a web of circuits in the brain. This is called structured knowledge. Learning is intended to create structured knowledge, not just to warehouse facts.

The Brain is Designed to Create and Connect Ideas

In a fascinating article in the Aug. 2006 Scientific American called “The Expert Mind” the author, Phillip Ross uses the game of chess to show how structured knowledge is created in the brain. Ross notes that

a typical grandmaster has access to roughly 50,000 to 100,000 chunks of chess information. (p. 69)

A chunk of information here refers to the layout of chess pieces on a chess board. Somehow the grandmaster stores 50,000 or more board layouts which he or she uses in strategizing their next move. This is not a feat of raw memorization. Rather, through playing many games of chess, the grandmaster has categorized different playing scenarios and how one leads logically to the next. If you interrupted play and asked for an explanation of how the grandmaster decides on the next move, you could get one. The grandmaster doesn’t just remember, he or she knows.

Development of this structured knowledge requires what Ross calls “effortful study” which he defines as

Effortful study . . . continually tackling challenges that lie just beyond one’s competence. (p. 69)

Repetitious physical workouts lead to stagnation and plateauing. If you want to keep getting stronger, more agile—whatever—you need to keep pushing by changing your workout regimen and your goals. Similarly, knowledge grows from a basic explanation of the facts in the bundle to increasingly deep levels of understanding; not just how, but why and from there to wisdom about what will happen when we employ this idea appropriately in some new context. All this happens as we continue to tackle challenges just beyond our current competence.

Mentally this looks like pulling up an idea and examining it by bringing additional information to bear on it. It also looks like pulling up two ideas to see if there is a relationship between them that I’ve previously missed. This is a relentless quest if you want to be a lifelong learner who will inspire your child. This kind of thirst for knowing inspires those around you.

With that background, let’s explore Daniel Willingham’s learning principle number 4: “We understand new things in the context of things we already know.”

Willingham starts chapter 4 with a surprising statement:

“Abstraction is the goal of schooling.”

Some education systems are suspicious of theory which means they have little patience with abstraction. Insistence that everything taught be immediately practical sabotages deep learning. To dismiss theory as ivory tower idealism is to miss out on powerful principles (which are abstractions) that are useful in many different contexts. Putting it another way, many things look like a one-off until you realize there are common elements in the different specific contexts and those commonalities lead to the creation of an abstraction with better ability to explain, predict, and control. It is equally true that a failure to regularly apply abstractions leads students to assess them as practically irrelevant. That also destroys the motivation to learn.

In previous podcasts this season we’ve seen that the information orientation which focuses on facts kills motivation by failure to foreground the question the facts will be used to answer. It also focuses on fact retrieval rather than creating fact bundles through explanation. These ideas are the fuel of thinking. What facts belong in the bundle? How are they related? Constructing ideas is all about a fixation on asking questions rather than just retrieving other people’s answers. We’re not good at asking questions, but this is an area where your growth will directly catalyze learning in your child. I’ll link to resources about questioning in the blog post for this podcast. You can go to deepanddurable.com for those links.

I hope the distinction between information and ideas is clear because I’m now going to wade into two of Willingham’s worst paragraphs as he begins chapter 4. On p. 96 he says,

In Chapter 2 I emphasized that factual knowledge is important to schooling. In Chapter 3 I described how to make sure that students acquire those facts – that is, I described how things get into memory. But I’ve also assumed that students understand what you’re trying to teach them. …What do cognitive scientists know about how students understand things?

The answer is that they understand new ideas (things they don’t know) by relating them to old ideas (things they do know).

These paragraphs are a mess! In the interest of my blood pressure and your tolerance for my ranting, I’ll keep the dispute focused.

Notice how often Willingham uses the indefinite term “things” in these paragraphs. “How things get into memory.” “How students understand things.” “Things [students] don’t know.” “Things [students] do know.”

A thing is a very large category.

It lacks precision and that invites confusion.

When Willingham says, “How things get into memory.” He is talking about his chapter 3 riffs on getting facts into memory. As I said in the last podcast, you can only do that by rote memorization.

When he says, “How students understand things.” Willingham is talking about understanding ideas.

Willingham rightly exalts understanding on p. 96. The heading says,

“Understanding is disguised remembering.”

That’s another way of saying that memory is the residue or byproduct of thinking. You think about ideas. You understand ideas. By contrast, facts are true statements that can be retrieved without understanding them. If I have an idea, I can test it with facts. If facts collide with my idea, probably (but not always) my idea is incorrect. Ideas bundle related facts and provide an explanation for their relationship. Fact bundles are created as I recognize patterns that suggest a relationship.

Not every true statement is a fact. Ideas should also be true. Facts are inert. Facts may be retrieved but only following an appropriate prompt. In contrast, ideas are brimming with the possibility of personal understanding and potential creative application.

Panama Canal Image by Andrea Spallanzani from Pixabay

It’s a fact that Jimmy Carter was responsible for transferring ownership of the Panama Canal to Panama through a treaty ratified by Congress in 1978 and it’s a fact that Donald Trump wants to take it back. You can memorize all that and not be able to reckon with why the U.S. owned the canal in the first place, why we would cede ownership to Panama, and why Donald Trump wants it back. Answering all those why questions requires a process of justification that demonstrates understanding of ideas. Memorizing the history of ownership and control is not knowledge because you can repeat facts without understanding the ideas that are behind the history.

Facts and ideas are not synonyms.

Fact don’t require justification. They just are. You don’t need to reason 1978 into your memory as the date Panama was given ownership of the Panama Canal. If that’s all you’re trying to do, the brain is not very good at recall. Getting that date into memory is by brute force, by rote. On the other hand, it is possible that 1978 as a fact may tag along as you understand the concept of U.S. ownership of foreign properties and what was behind Jimmy Carter’s perspective. That’s an idea. Students don’t understand “things;” they can understand ideas with some targeted thinking.

This conflation of information (that is facts) and ideas is both epidemic and deadly. This lack of clarity is also behind the amorphous terms “content” and “material” that I warned you about in the previous episode. Clarity is a prerequisite to understanding including understanding about how we learn!

In this episode I’m working on the development of ideas because only ideas have the potential to be understood. Ideas are abstractions. I have to disagree with Willingham when he says, “the mind seems not to care for abstractions. The mind seems to prefer the concrete.” p. 95

Building abstractions out of concrete instances is something we’ve been doing since we were born and possibly before. It’s what the brain was designed to do.

We build abstractions out of the concrete

Physical items are obviously concrete and that’s where we focused when we were very young. We encountered many different dogs of widely different size, appearance, and demeanor. Some were aggressive. Some had a bark that was comical. Some were ugly, some were cute. Regardless, they are all securely catalogued in our minds as instances of the category we label dog.

Emotional states can also be collected in categories. How they are exhibited depends on the person. You learn to read people. Take anger - some people lash out when they are angry and some clam up. Some in the latter group give away their emotion by their facial expression or their red face and some look placid by dint of self-control but are every bit as angry. Slowly we develop our concept of anger and learn to detect it so we can respond to it wisely.

The concept of ownership is developed in a rudimentary form when we are quite young. Children cry or hit other children when one of their toys is picked up or perhaps even touched by another child. This is a far cry from ownership of the Panama Canal, but the latter is clearly a more developed form of “that’s mine” in young children.

Part of our claim on the Panama Canal is that we built it. Construction as building something is established as an idea early in life. Stacking blocks into towers builds hand-eye coordination, but it builds a concept as well. Putting smaller pieces together to make something bigger and more complex is the root idea of construction and two-year olds get this much.

The main point here illustrates Willingham’s Principle #4: “We understand new things in the context of things we already know, and most of what we know is concrete.”

A principle as I’ve tried to clarify in my book explains, usually in terms of cause and effect. In that respect, I think Willingham’s Principle #4 is a bit vague. It is vague first because it uses the label “things” when it should use the interchangeable terms concept or idea. It is also vague when it refers to “in the context of things we already know.” That describes an environment where concepts are developed, but not the real cause.

Here's my replacement (a real principle):

We construct new concept categories by looking for concrete instances that show a pattern that doesn’t fit our existing concept categories.

Construction is personal and idiosyncratic. I detect what I think is a pattern—a regularity in properties. Then I look at my existing categories to see if this pattern has already been recognized and incorporated into an existing category. If I can’t find such a category, I tentatively group these instances together as a new concept which I then label with what the language offers as a plausible label. This creation of new categories–ideas or concepts - goes on constantly. At part of the process, I pull up an existing category from long-term memory into working memory to see if the existing idea can accommodate the new examples. If so, I don’t need to. create a new category. That process also offers some interesting opportunities for detecting potential analogies. An analogy is an instance where part of the pattern I’m seeing in one category is also true of a very different one.

If we go back to the concept of construction and explore constructing a house, there are interesting parallels in how a house is built and how cells in living organisms are built. One layer is that houses reflect a design that is specified in a blueprint. The blueprint in cells is the DNA. Specific building materials need to be delivered as specified by the blueprint and that is the job of something called transfer RNA. I could go on, but I won’t. Eventually the analogy gets a bit strained, but it is useful because building a house is much more concrete and visual than building the microscopic structures of a cell. Concreteness is what the novice learner craves in order to create increasingly sophisticated abstractions. Help your child find concrete analogies that will scaffold their growing understanding. Ask them questions that will help them discover what is parallel and where the analogy breaks down. Our brains are designed to leverage the concrete in the service of the abstract.

Outro:

How is your coaching career going, parent? Questions are your primary tool, but you are not an inquisitor. Keep it light and don’t press. Give your child space to think about your questions. More wait time equals better answers.

Emphasize the positives you are seeing as your child gets curious about ideas that make sense out of a fact-focused curriculum.

I’d love to hear from you about the personal benefits of these podcasts as well as continuing challenges. You can contact me at my website deepanddurable.com

In this episode we talked about constructing new ideas and connections using what we already know. This is a disposition that develops over time.

Willingham’s principle number five is:

“Proficiency requires practice.”

How can you keep developing your child’s framework of ideas without creating boredom or resentment? We’ll explore that in two weeks.

Never stop learning!

Resources for asking better questions from Mike Gray:

Podcasts: Season 5 “A Way of Thinking”

Perspective Produces Questions

Formulating Compelling Questions

Answering Questions by Asking Questions

Blogs:

Perspective Produces Questions

Questions are the Engines of Thought

Formulating Compelling Questions

Answering Questions by Asking Questions

My Book:

Unforgettable: Enabling Deep and Durable Learning (Chapter 8, “Ask, Don’t Tell”)

Warren Berger: https://amorebeautifulquestion.com/