Formulating Compelling Questions

Child Image by AURELIE LUYLIER, You're Welcome! from Pixabay

Questions power thought. There is no real thinking unless there is a question propelling it. While we may be intrigued by a question that someone else has asked, the best questions are the ones we generate.

Generating compelling questions is a joint venture pairing your personal point-of-view with what motivates your question. Your motive may be to solve a simple problem of ignorance, but really compelling questions are motivated by deeper concerns and usually start with “why.”

What follows is an approximate transcript of the podcast Formulating Compelling Questions in the Core:

In three podcast episodes earlier this season, I took apart the thinking process into nine components which are organized into three layers. Thinking begins in the layer I call the core, proceeds to the working layer where we do most of our chewing on questions, and leads to the output layer where our conclusions and anticipated actions come out.

The entire thinking process is propelled by questions. Indeed, questions are the engines of thought. Starting today and continuing in the two concluding podcasts of this season we’ll revisit these layers and learn how to ask the kind of compelling and clarifying questions that will make our thinking what it ought to be.

I want to be very concrete today. Let me start with an article from today’s NYT. Written by opinion columnist Pamela Paul, it is provocatively titled “How to Get Kids to Hate English.” Obviously, no parent and certainly no teacher would set out with this goal in mind, but Paul argues we have managed to make most kids hate English. One of my sons has an undergraduate degree in English as well as masters and doctoral degrees in English. As a counter argument to the article, one of my grandsons who will enter college in the fall has declared that he will be majoring in English. My grandson has been homeschooled all his life.

Pamela Paul points to the way English is taught in middle and high schools as a major reason that kids hate English, especially reading literature. As she puts it, “It’s as if once schools teach kids how to read, they devote the remainder of their education to making them dread doing so.” Paul says the literature kids are forced to read is insipid and undermines the very possibility of creating a love of the power of narrative to transport, inspire, and transform.

I’ll link to the article in the accompanying blog post at deepanddurable.com.

The core of thinking is where we generate questions that we care enough about that we are willing to wrestle with them at length in the working layer. We generate questions to solve problems whether problems of ignorance, conflicts between systems of thought, or practical problems of all stripes. We generate these questions from a point of view and with a motive—what we are trying to accomplish through our thinking.

Because formal schooling privileges answers, most people are used to accepting propositions without questioning them. This is a serious mistake. It makes as much sense as fueling a vehicle that has no engine under the hood. Propositions can be valuable, but only to the extent that they provide fuel for reasoned argument. Questions are the engines of argumentation. The best questions are self-generated, but all questions must be articulated or thinking has no engine. Learning is not accumulating propositions; it is achieving understanding through grappling with questions.

When questions do come up in written argumentation, most of us treat them as rhetorical and not as a summons to provide an answer. When teachers ask questions in live instruction, the students don’t answer (1) because the question is surely rhetorical and (2) because the average teacher answers their own question within two seconds!

This comes up also when Christians engage in so-called serious Bible study. Rather than wrestling with a passage and generating their own questions, the average believer reads the passage as propositional truth and then reads the commentaries to see what theological thinkers have written about it (more propositions). Even those who personally generate a few questions from a passage look to commentaries to resolve the questions rather than wrestling with the questions personally. This short-circuits learning. Commentaries should only be consulted after individuals have extensively grappled with the biblical writer’s argument.

Let’s go back to “How to Get Kids to Hate English.” The author confesses to a love for great classic literature that is no longer typical of students. This is a point-of-view, a perspective. You could certainly say this perspective carries with it a bias as all perspectives do. The bias here assumes what was fulfilling and transforming for her is generally true. The Great Books or Classical approach to the Western Canon of literature has had many advocates over several centuries. One major question emanating from this perspective is, “How can we utilize great literature to maximize the creative problem-solving ability of students?” What other perspectives on this issue are there? There is the economic point-of-view which emphasizes employability as the main rationale for education. The question here is, “Does the English curriculum make it more likely that the student will be able to get a good job?” This vocational pragmatism is a major driver of education all the way from kindergarten through college. The Common Core approach to education puts a premium on standardizing curriculum and getting as many students as possible to pass the related standardized tests around which the system revolves. Common Core advocates might ask, “How can we produce a literature curriculum that we can get consensus about, and that faculty can teach so as to consistently reach student performance benchmarks?” A fourth perspective emphasizes present-day relevance arguing that reading dead white males is irrelevant. What is relevant from this point-of-view is literature that reflects current cultural norms and reading works that don’t argue in ways that may cause angst and offense. For these folks the question might be, “How can literature choices assure students absorb current cultural norms and reject old, distorted ways of thinking?”

From this quick survey of perspectives on the issue of how to teach English literature, we can see that there are multiple perspectives representing multiple stakeholders—and I haven’t mentioned parents or the students themselves! Wrapped up with each point-of-view is a motivation that shows up in the question each generates. By motivation I mean what each is trying to accomplish with their thinking about the issue. You can back up and listen to each question again and detect at least some of the motivation underlying each one. The issue is best addressed by looking at it through all of these lenses, albeit one-at-a-time. I don’t believe that all perspectives are equally valid, but it is important that our handling of the issue be multi-dimensional and not simplistic or overly influenced by personal experience.

I think it is important here to circle back around to beginner’s mind—the wide-eyed wonder and boundless curiosity you had in your early childhood. Cultivate that humble state of mind that wasn’t afraid to appear naïve. Cultivate the spontaneous inquiry that led regularly to the joy of discovering satisfying answers. Beginners can ask some really good questions! You don’t have to be an expert to be qualified to ask.

Expertise is often accompanied by the curse of not even thinking to ask certain kinds of questions. I was present at a scientific meeting decades ago when Richard Blakemore described his discovery of magnetosomes, structures which allow certain bacteria to orient themselves with the earth’s magnetic field. It would never have occurred to an expert that bacteria would need to know where north is in the northern hemisphere, but Blakemore was in his first semester of graduate school and had only one microbiology course as an undergraduate. His relative naivete allowed him to frame a question that would only occur to a beginner’s mind, “Why are these bacteria I’m observing under the microscope seemingly aligning themselves to magnetic north?”

Magnetotactic bacterium containing a chain of magnetosomes shown in red

While we’re considering the question-generating core of thinking, we should recognize that not all questions are good questions. Investing in the wrong question can lead us on a wild goose chase and waste precious time and cognitive energy. It is important to question your question. Is there a question that is more basic (that is foundational) to the one I’m asking? Is the question clear? Is the question logically connected to my point-of-view or is it really derived from a different perspective? Is the question really looking for an answer or is it loaded with presuppositions that reflect my certainty that my perspective is correct? Why ask a question if you already know the answer?

The four questions I proposed a few minutes ago for four points of view on teaching English literature could be improved if they were reformulated. They are slanted questions that prematurely rule out exploring alternatives. The real question is bigger. The big question underneath all these specific questions is something like, “Why has interest in and facility with English markedly declined over the past 10-15 years?” Starting a question with “Why” is almost always a smart move—ask any 4-year-old.

Let’s try to formulate the question about CO2 I promised two weeks ago. This question will drive the final episodes of this season. I’m approaching this question from an ecological perspective as one trained in microbial ecology. Don’t worry, you’ll hardly notice! My motivation is to try cut through the propaganda surrounding this issue; propaganda which insists that anyone who asks questions is probably a skeptic, if not a denier. Asking questions without a precommitment to a particular conclusion is in fact inquiry in pursuit of deep understanding, not rabble rousing.

Questions don’t come out of thin air, so a bit of background first to set some context. The EPA web page that deals with greenhouse gases makes this summary statement: “Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the primary greenhouse gas emitted through human activities. In 2020, CO2 accounted for about 79% of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from human activities. Carbon dioxide is naturally present in the atmosphere as part of the Earth's carbon cycle.”

A few clarification questions will help us craft the right compelling question to sustain us when we get in the working and output layers. First, “What makes something a greenhouse gas?” The EPA says, “Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are called greenhouse gases.” Air is 78% nitrogen followed by 21% oxygen. That’s 99% with just two gases, neither of which is a greenhouse gas. The remaining 1% is a mixture of other gases including neon and hydrogen. CO2 amounts to about 0.04%.

Emission technically means “to give off,” but connotatively it often impugns the thing emitted as a pollutant. CO2, on the other hand, is “naturally present in the atmosphere as part of the Earth’s carbon cycle.” Indeed, humans and all other living organisms “emit” carbon dioxide constantly. CO2 is emitted every time we exhale. CO2 is produced through cellular respiration as we break down food molecules to make their energy available to our cells. Virtually all life forms do the same, including plants.

There is widespread confusion about photosynthesis. Plants and other photosynthetic organisms (most of which are bacteria) perform both photosynthesis and cellular respiration. Plants use carbon dioxide and the energy of sunlight to synthesize all their organic molecules including food molecules. Those food molecules are then broken down using cellular respiration to produce—you guessed it—carbon dioxide!

This is a far cry from the popular mythology that animals produce carbon dioxide and plants use that carbon dioxide. Plants can take in CO2, but they also produce it.

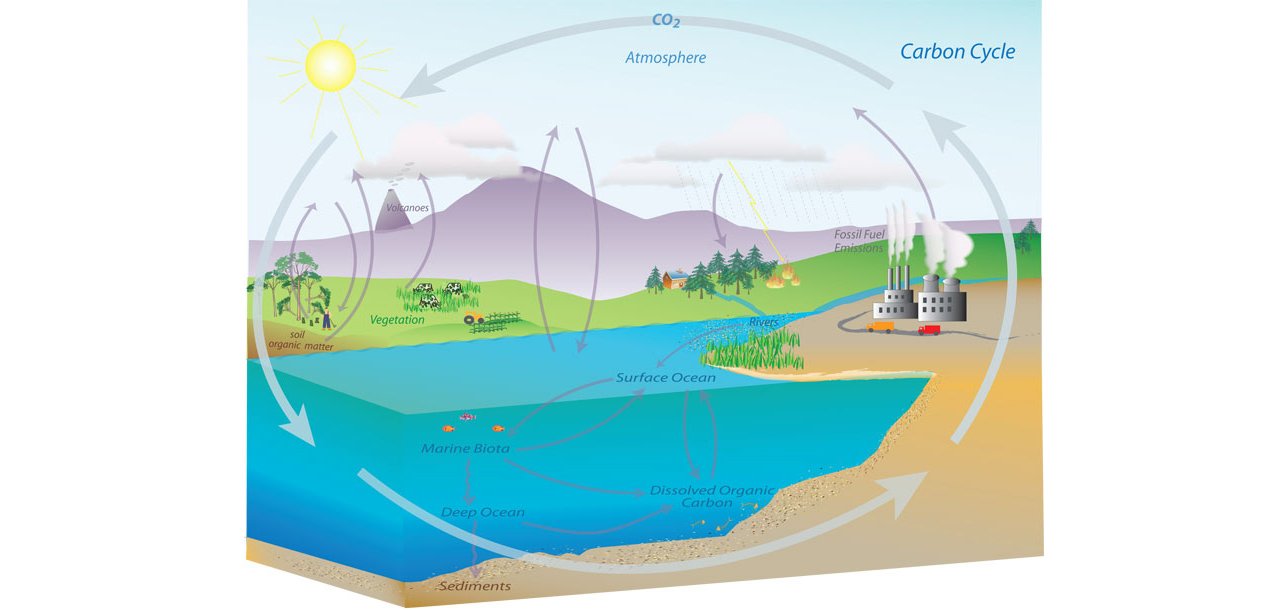

As a natural cycle the carbon cycle—cycles! It goes around and around as it was designed to do. Here’s an excerpt from a video produced by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration):

“What is the carbon cycle? Carbon is the chemical backbone of all life on Earth. All of the carbon we currently have on Earth is the same amount we have always had. When new life is formed, carbon forms key molecules like protein and DNA. It's also found in our atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide or CO2. The carbon cycle is nature's way of reusing carbon atoms, which travel from the atmosphere into organisms in the Earth and then back into the atmosphere over and over again.”

The carbon cycle is an example of a biogeochemical cycle. Practically speaking this means that biologists, geologists, and chemists all have interlocking perspectives which are all necessary to adequately explain how the cycle functions.

Carbon cycle courtesy of NOAA

There is much more that could be said in developing a conceptual framework, but I hope this simplified version will suffice as the basis for formulating our focus question. In the episode in two weeks on the working layer, I’ll develop additional concepts.

Since humans constantly exhale CO2 produced from metabolizing our food, it follows that we are emitters of this greenhouse gas. Emission is inevitable. At about 2.3 lbs of CO2 per person per day, the current population on earth releases about 3 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year. This compares with 34 billion tons per year from burning fossil fuels.

Despite these facts, most climate scientists do not consider humans intrinsic polluters. How can this be?

See here and here for examples.

Here’s our focus question: Why is it pollution when we burn fossilized organisms and release CO2 and yet living organisms which constantly release CO2 are not a problem?

I hope you see the conundrum. I submit this as the focus question that will move us into the working layer in two weeks as we seek an answer. In the next episode, we’ll acknowledge assumptions we bring to the thinking process and whether they are reasonable. I’ll surface relevant facts—inconvenient and otherwise—which our thinking must accommodate or discredit. Finally, I’ll develop some concepts to enrich the network of ideas we will use in search of an answer. In the process of answering this question we’ll need to ask a bunch of other questions—that’s always true because questions are the engines of thought! See you in two weeks!