Everything is Connected

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Americans aren’t good readers, and the primary reason is that they don’t have the broad knowledge base needed for reading comprehension. Cognitive psychologist, Daniel Willingham a specialist in reading, makes this startling assessment and then calls for “significant changes in schooling” as the necessary response. He maintains,

“The systematic building of knowledge must be a priority in curriculum design.”

This “systematic building” should focus first on accurate concept formation and then on forging appropriate connections between concepts. In the last blog post we focused on recognizing patterns in objects or events as the basis for concept formation. But concepts don’t exist in isolation; they are highly interconnected. The interconnections between concepts are not merely associational, they are logical and, often hierarchical.

Concepts don’t exist in isolation; they are highly interconnected.

In the simple example of apples that we used last time, there are a multitude of other concepts that link with and enlarge the idea of an apple. A very basic list would include fruit, trees, orchards, ripening, and picking. These are all concepts, but they intersect with the idea of an apple. All the ideas on the basic list are “bigger” ideas than the idea of an apple. These bigger ideas connect to additional concepts besides the apple. Put another way, an apple is a pattern that intersects with other, broader patterns.

Neuroscientist Daniel Bor observes,

There is a remarkably common tendency for information stored on one level to combine to create a richer concept [network of concepts] at a higher level.

Bor continues, “In some cases, further layers can be constructed on these foundations of foundations, and so on, until an efficient yet towering edifice is created. . . . it leads to humans developing categories, plans, language, and ingenious strategies to serve, modulate, and enrich our emotions and motivations.” This approach works, Bor says, because “information in the universe is brimming with patterns.”

The “systematic building of knowledge” is not the mere accumulation of pigeon-holed facts. It also not the enlargement of a working vocabulary. Concepts are accessed by means of language labels, but retrieval may only access an empty shell or a shell containing a memorized definition, rather than a rich, mature concept.

The vice of “verbalism” can be defined as the bad habit of using words without regard for the thoughts they should convey and without awareness of the experiences to which they should refer. It is playing with words.

Mortimer Adler, How To Read a Book, p. 128 (emphasis mine)

Effective instruction must intentionally engage students individually in concept construction and enlargement. This requires inductive thinking. “In traditional instructional models teachers cover—rather than asking students to uncover—conceptual. . . understandings.” McTighe and Silver, p. 14 (emphasis original)

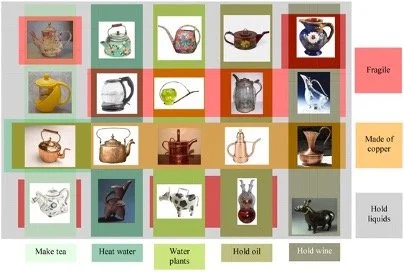

Neuroscientist Matthew A. Lambon Ralph and his colleagues use the concept of a container for fluids in this figure to illustrate the complexity involved in conceptualization.

Enlargement available via original pdf below

All the containers are designed to hold liquids. However, some are fragile, and others are quite durable. Some can be used to heat water, while others can only hold previously heated water to brew tea. Probably some of the vessels for watering plants can’t tolerate hot water. Follow the color codes to trace the various patterns as to properties and intended use and you’ll see patterns, but not simple patterns.

How are students expected to learn concepts? McTighe and Silver observe, “Instead of defining concepts for students, teachers challenge students to define those concepts for themselves by comparing examples and nonexamples to determine the critical attributes. [inductively]. . .it mimics the way we naturally come to understand and define new concepts.” (p. 15—emphasis original) A helpful tool to keep students from veering off onto rabbit trails is the use of focus questions that they are trying to answer as they explore the options you give them. These questions are intended “to awaken, not ‘stock’ or ‘train’ the mind.” (p. 10—McTighe and Silver quoting Wiggins, 1989) . In short, focus questions arouse curiosity by targeting knowledge gaps.

Let me return to an idea from the previous blog. Our brains naturally seek patterns from information and register as concepts the patterns they perceive. We all have a raw talent for concept formation, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get better—much better—at it. The quality of our thinking is directly related to the quality (depth and accuracy) of our concepts. If we never critically evaluate our concepts (and most people don’t), we will often be building our thinking on a faulty foundation riddled with misconceptions.

The quality of our thinking is directly related to the quality (depth and accuracy) of our concepts.

Concepts do not exist in isolation from other concepts. Elaborate and unexpected linkages exist between many seemingly disparate concepts. As an example, I recently watched an excerpt of an episode of the PBS series, American Experience, called “Riveted: The History of Jeans.” It was captivating.

What we call denim may have origins in India, or Italy, or France as early as the 1600’s. Production of jeans in the U.S. involved growing cotton as well as the plant used to dye it, indigo, in the South using slave labor. Slaves were often clothed in blue denim as were manual workers of all kinds including, yes, cowboys. In the late 1940’s blue jeans became associated with rebellion. The plot thickens from there. Curious? Watch the whole broadcast! The point is that the story of blue jeans logically connects to ideas that initially and superficially appear to be unrelated. That’s the nature of knowledge construction. It’s a feature, not a bug. The pursuit of understanding inevitably and regularly leads to surprises which create curiosity leading to the motivation to learn.

In knowledge construction, you are obliged to define the relationship between pairs of ideas.

Ideas should be linked to other ideas to form logical, defensible propositions. A proposition is a statement about the nature of the relationship between two concepts. It is not enough to simply associate the two ideas. In knowledge construction, you are obliged to define the relationship. Concept A might be more general and include concept B. On the other hand, concept A might cause concept B (which would be the effect).

An example of both relationships is the concept of an infusion. An infusion is a hot water extract of plant and/or animal tissue. Coffee, tea, and soup are all types of infusions. There is a hierarchy of classification which relates the examples to the infusion category and there is a process involved (hot water extraction) which results in a soup or a beverage.

Branching patterns of relationships between a variety of concepts approximates what happens in the brain. The brain recognizes patterns to create the concept itself and additional patterns that justify where the concept resides in the overall neural conceptual framework.

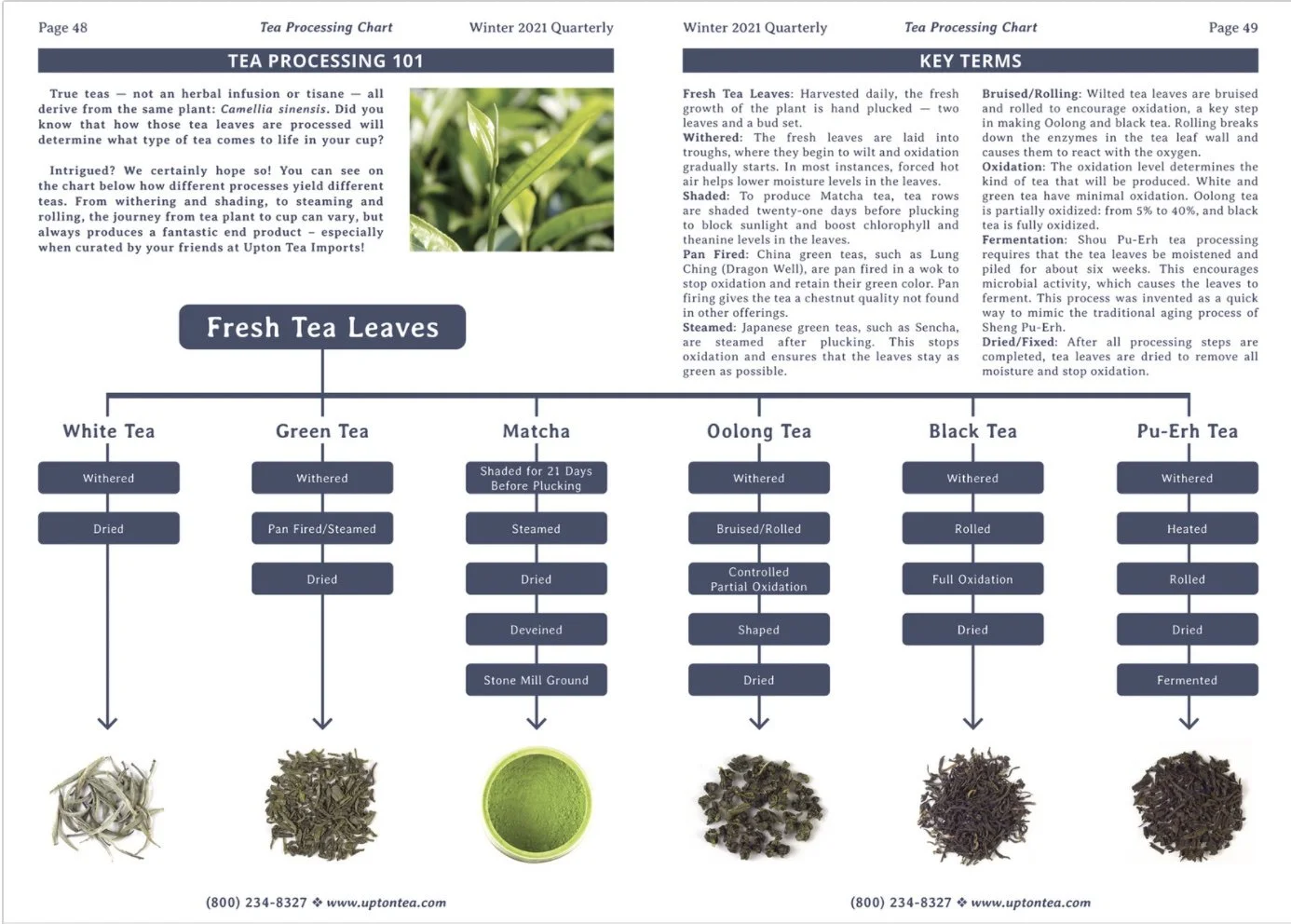

Look at this diagram explaining the relationship of the various kinds of tea:

What you should notice here is that all true teas come from the leaves of the same plant, Camellia sinensis. The difference between green tea and black tea is in how the tea leaves are processed. The same is true for all true teas. The processing of the leaves always includes withering the leaves (except for Matcha tea). The concept of withering and how it is carried out is explained in the diagram as are a variety of other processes (concepts) that determine the final product. Of course, to purists where the tea is grown and the soil, rainfall, average temperature, and a host of other environmental factors determine how the tea tastes.

To demonstrate the additional concepts logically linked to tea, we could consider the type of water used for brewing, the apparatus for heating the water, the temperature of the water used for brewing tea, the length of time for brewing, whether loose tea or bags (sachets) are used, and the nature of the tea service (pot and cups).

When I ask my wife on a cold winter morning if she would like a cup of hot tea, all of this and more is referenced in the conceptual frameworks in both of our brains. “In neuroscience, semantic memory or conceptual knowledge refers to the font of information we possess that enables us to bring meaning to [hot tea!] words, objects, and all other nonverbal stimuli (e.g., smell, sounds, etc.). . . .there is no mystery about where semantic knowledge comes from— it derives directly from the totality of our verbal and nonverbal experience.”

Perhaps you should grab a cup of your favorite hot beverage and peruse the resources on concept mapping below. This is the mental exercise equipment that can maximize your growth in deep and durable learning this year!

Mental Fitness Equipment and Workouts:

Making Your First Concept Map (pdf): Your First Map

Free Concept Mapping Software: Concept Mapping Software

Helpful Information About Concept Maps: Documents to Start Concept Mapping

Check out Unforgettable: Enabling Deep and Durable Learning, my 2016 book. Chapter 4 is an extended how to on conceptualization and concept mapping.

Don’t feel like a workout right now?

Check out this striking short video showing the brain using musical patterns to create satisfying emotion. Being cerebral isn’t always about effort. Enjoy!

Sources:

Daniel Willingham: How to Get Your Mind to Read

Daniel Bor: The Ravenous Brain

Jay McTighe and Harvey F. Silver, Teaching for Deeper Learning: Tools to Engage Students in Meaning Making

“Coherent concepts are computed in the anterior temporal lobes,” Matthew A. Lambon Ralph, Karen Sage, Roy W. Jones, and Emily J. Mayberry, PNAS | February 9, 2010 | vol. 107 | no. 6 | 2717–2722. Access here